Sensing China Threat, India Joins Race To Mine New Sea Patch

India seeks to explore a cobalt-rich region in the Indian Ocean known as the Afanasy Nikitin Seamount

Earlier this month, India applied to the International Seabed Authority (ISBA), Jamaica, for rights to explore two vast tracts in the Indian Ocean seabed that aren’t part of its jurisdiction. The application to explore one of these regions, a cobalt-rich crust long known as the Afanasy Nikitin Seamount (AN Seamount), is a gambit by India. Rights to the region have already been claimed by Sri Lanka under a separate set of laws, The Hindu has learnt, but India’s application is part-motivated by reports of vessels by China undertaking reconnaissance in the same region, a highly placed official, who declined to be identified, reported The Hindu.

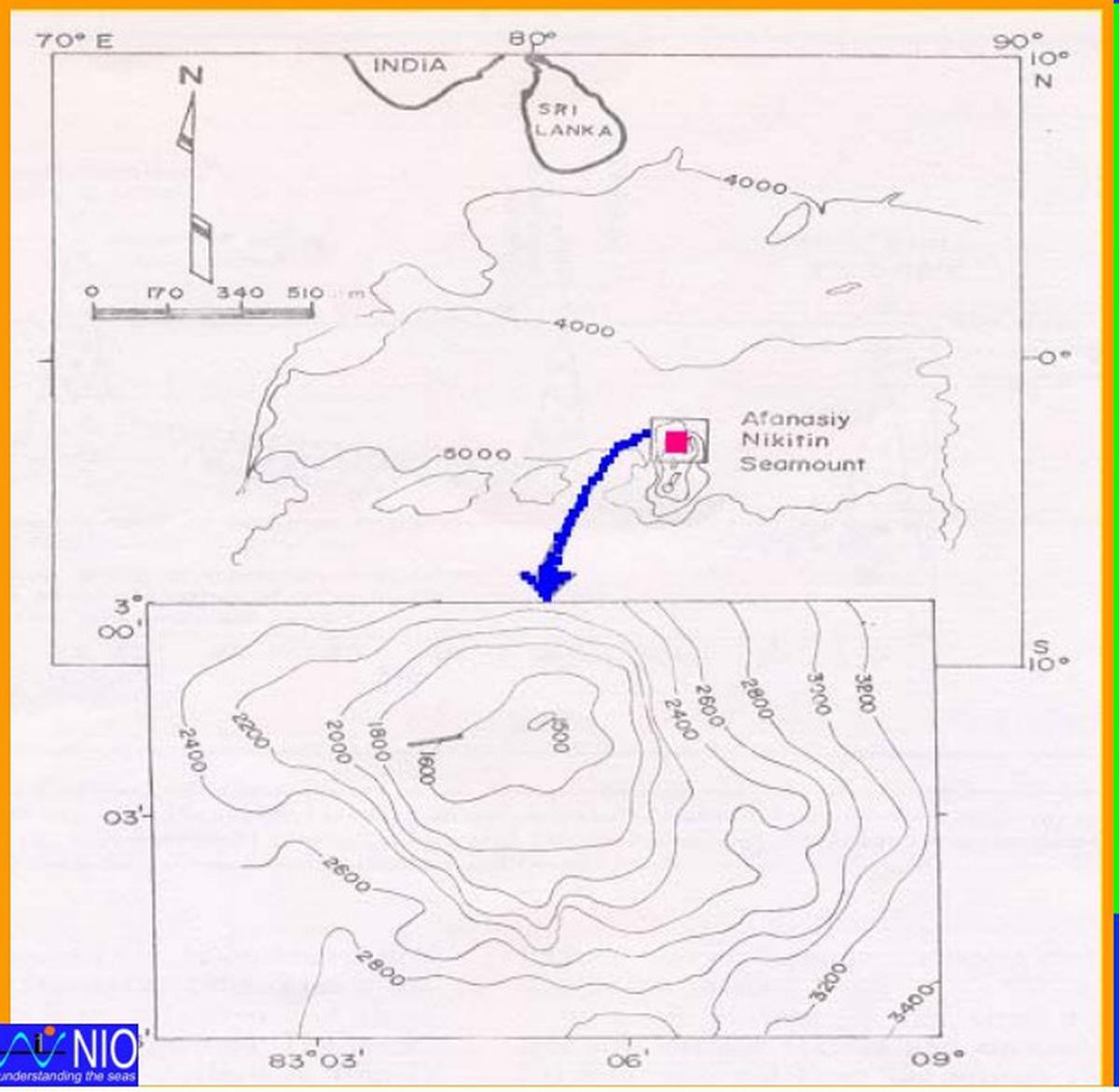

The AN Seamount is a structural feature (400 km-long and 150 km-wide) in the Central Indian Basin, located about 3,000 km away from India’s coast. From an oceanic depth of about 4,800 km it rises to about 1,200 metre and — as surveys from about two decades establish — rich in deposits of cobalt, nickel, manganese and copper. For any actual extraction to happen, interested explorers — in this case, countries — must apply first for an exploration licence to the ISBA, an autonomous international organisation established under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

The AN Seamount is located about 3,000 km away from India’s coast. Photo: www.isa.org.jm

These rights are specific to areas that are part of the open ocean, meaning ocean — whose air, surface and sea-bed — where no countries can claim sovereignty. Around 60% of the world’s seas are open ocean and though believed to be rich in a variety of mineral wealth, the costs and challenges of extraction are prohibitive. Currently no country has commercially extracted resources from open oceans.

However, another UNCLOS-linked body, the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, which decides on the limits of a country’s continental shelf, may impede India’s exploration ambitions.

Exclusive Rights

Countries have exclusive rights up to 200 nautical miles, and its underlying sea-bed from their borders. Some ocean-bound states may have a natural stretch of land, connecting their border and the edge of the deep ocean that extends beyond this 200, as part of their so-called continental shelf. To claim so, however, a country must give a detailed scientific rationale, complete with underwater maps and surveys to show this unbroken land-connect to a scientific commission appointed by the ISBA. If such a claim is approved, then such a country will have primacy to explore and potentially exploit the living and non-living resources in the region.

Normally, claims to the continental shelf do not extend beyond 350 nautical miles from their coast. “However, there is a provision under which countries along the Bay of Bengal can apply a different set of criteria to make claims on the extent of their continental shelf. Using this, Sri Lanka has claimed up to 500 nautical miles. Whether they are actually awarded so we have to wait and see but India has staked a claim for exploration because we have noted Chinese presence. If we don’t at least stake a claim now, then this could have consequences in the future,” the official told The Hindu.

If a region isn’t formally classified as being part of a country’s continental shelf, then it is considered ‘high sea’ and open to any country to approach the ISBA and ask permission for exploration.

“For the application for cobalt-rich ferromanganese crust, the Commission noted that the area of the application [by India] lies entirely within an area submitted to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf by another state [Sri Lanka]. The Commission has sought comment in writing from the applicant [India] on this matter,” says a report by the ISBA based on proceedings this month and available on the organisation’s website.

A high-level delegation from India led by the Ministry of Earth Sciences was in Jamaica, the ISBA headquarters, this month, presenting scientific evidence to buttress India’s claims to exploration. The ISBA has in turn asked India to clarify on multiple points. A final decision is expected later this year. Along with the application for AN Seamount, India has also applied for permission to explore another region, spanning 3,00,000 square km, called the Carlsberg Ridge in the Central Indian Ocean to investigate for polymetallic sulphides, which are large smoking mounds near hydrothermal vents that are reportedly rich in copper, zinc, gold and silver.

Like Sri Lanka, India too has staked a claim for its continental shelf up to 350 nautical miles from its border but has yet to be awarded so. It has previously garnered exploration rights to two other large basins in the Central India Ocean and has undertaken surveys.

India applied to the International Seabed Authority (ISBA), Jamaica, for rights to explore two vast tracts in the Indian Ocean seabed that aren’t part of its jurisdiction. The application to explore one of these regions, a cobalt-rich crust long known as the Afanasy Nikitin Seamount (AN Seamount), is a gambit by India.

The AN Seamount is a structural feature (400 km-long and 150 km-wide) in the Central Indian Basin, located about 3,000 km away from India’s coast. From an oceanic depth of about 4,800 km it rises to about 1,200 metre and — as surveys from about two decades establish — rich in deposits of cobalt, nickel, manganese and copper.

These rights are specific to areas that are part of the open ocean, meaning ocean — whose air, surface and sea-bed — where no countries can claim sovereignty. Around 60% of the world’s seas are open ocean and though believed to be rich in a variety of mineral wealth, the costs and challenges of extraction are prohibitive.