The Panic Buys

Arming Up: Defence minister Rajnath Singh and his team at a meeting during their Moscow visit in June

As the Himalayan stand-off between the Indian Army and the People’s Liberation Army of China in eastern Ladakh entered its fourth month, the country’s armed forces embarked on a fresh round of emergency fast-track procurements (FTPs) of weapons and ammunition to replenish their arsenal. The defence ministry is buzzing with activity as files and proposals are being drafted for approvals in South Block with a speed that only crisis brings.

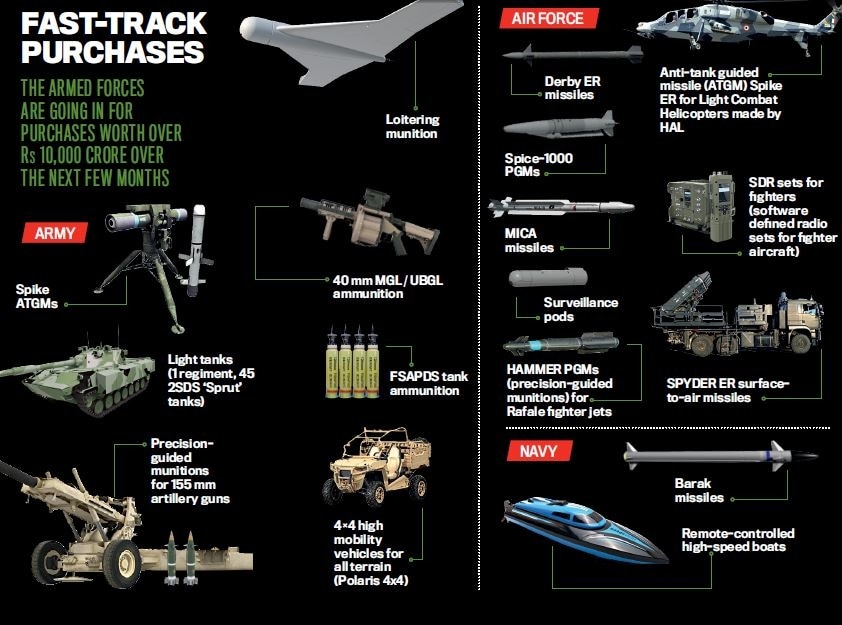

On the anvil are a slew of weapon imports, including light tanks, tank ammunition, surface-to-air missiles, assault rifles and drones, estimated at over Rs 10,000 crore from three of India’s biggest defence suppliers, Russia, the US and Israel. The weapons are meant to equip the army and the air force forward-deployed in Ladakh since late May. On July 16, the defence ministry allowed emergency procurements worth Rs 500 crore for each of the three services, with no restrictions on the number of such programs.

The army, which has deployed four divisions in the theatre of action, has the most numerous requirements. It wants kamikaze drones, anti-tank guided munitions, shoulder-fired missiles, high-mobility vehicles and GPS-guided shells for the newly-acquired ultra-light howitzers, and even ammunition for small arms (see Fast-Track Purchases). The air force wants additional shipments of Derby and MICA air-to-air missiles and Spice-1000 precision-guided munitions for its fighters. Rather than wait to integrate Israeli munitions on its Rafale fighter jets, it has opted for French Hammer precision-guided munitions to equip its first five jets flying in from France, literally into the thick of action, on July 29. A defence ministry official indicated that almost 100 cases are in the contractual process, to be concluded by the end of the current financial year, March 2021.

The Road Less Taken

The world over, defence purchases are a cumbersome process lasting several years. In India, the byzantine procurement process involves the civil and military bureaucracy as well as the political leadership, which means it could take even a decade to purchase anything from a sophisticated fighter jet to a bulletproof jacket. The armed forces have to identify requirements, look for hardware that meets their needs, conduct extensive trials and finally invite competing bids from global suppliers. The arrival of the Rafale jets is the culmination of a process that began soon after the 1999 Kargil War, with the contract finally signed in 2016.

Emergency FTPs, which shorten the defence ministry’s cumbersome weapons acquisition processes, first began during the Kargil War. The army found its ammunition stocks insufficient to last even that short border conflict. Artillery, essential for softening up enemy targets before soldiers can move in, relies on a constant supply of ammunition. A 155 mm Bofors gun, for instance, requires at least 250 shells per day to fire in an offensive mode. In Kargil, even as Indian artillery trained their gunsights at features like Tiger Hill and in Batalik, army and defence ministry procurement teams were flying into Cape Town and Tel Aviv to top up the depleting stocks of shells.

The FTP, a beguiling enemy-at-the-gates syndrome, has been a feature of every military crisis ever since. The purchases triggered by the ongoing Ladakh stand-off would be the third occasion in recent years when the armed forces went on an emergency weapons and ammunition-buying spree. FTPs had also followed the cross-border raids by Indian forces in the aftermath of the September 2016 Uri terror attack and the February 2019 air strikes in Balakot, when India and Pakistan once again teetered on the brink of a conflict.

An army official explains how FTPs and the delegation of emergency financial powers are helpful. Between January 2014 and October 2016, the army concluded 20 contracts valued at Rs 400 crore. When the delegation of powers happened in 2016, the army did contracts worth Rs 11,000 crore. “It gave a big boost to this model and revived the government’s confidence, and therefore, it was allowed to go beyond the stipulated time and 40 more contacts worth Rs 4,500 crore were done through this process,” says the official.

FTPs can be explained by India’s heavy and continuing dependence on imported military hardware. The country was the world’s second-largest importer of arms in 2014-18 and accounts for 9.2 per cent of the global arms sales.

Indian armed forces are among the five largest in the world. At $71 billion, India’s defence budget in 2019 was only a fraction of what the US ($705.4 billion) and China ($261 billion) spent, but it was still the world’s third largest. The failure to create an indigenous military-industrial complex that would keep pace with a military machine and its requirements is what leads to imports of fighter jets, tanks and submarines. While these acquisitions significantly boost combat capability, they also leave the country vulnerable to imports. “Your capability to fight anything, from a local skirmish to a long war, is ultimately dictated by your domestic production capabilities,” says Lt General Sanjay Kulkarni, former director general, Infantry.

Government campaigns for self-reliance, Make in India in 2014 and Atmanirbhar Bharat in 2020, have not been turned into roadmaps towards achieving self-sufficiency in weapons requirements.

Among the early indications that the Ladakh stand-off was going to be a prolonged one, necessitating overseas weapons purchases, was defence minister Rajnath Singh’s visit to Moscow in June. Singh was there as a state guest at the Victory Day parade on June 24. He took along a defence ministry delegation, including the defence secretary, senior bureaucrats and military officials, and spent a full day meeting key members of Russia’s military-industrial complex and discussing urgent buys from India’s largest overseas supplier.

Indigenous The Way

Proponents of an indigenous defence industrial base say fast-track imports are like a foot in the door and gradually expand into larger orders, diverting limited budgetary resources. The army is close to placing a second order of 72,000 battle rifles from US arms-maker SIG Sauer, after an identical purchase last year. Indian manufacturers who have invested in developing domestic capabilities to design and develop small arms are aghast. “FTPs strike the biggest blow to Indian industry. When the armed forces go for foreign weapons, even small arms, you are effectively telling the world that your indigenous capacity is worthless. When we try and export, the first question we are asked is ‘why isn’t your own army buying your products’,” says the CEO of a private sector firm.

The Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) is worried that an order for a regiment (45 vehicles) of Russian 2SDS ‘Sprut’ light tanks for use in high-altitude terrains like Ladakh will kill its own under-the-wraps light tank project. The infantry wants more Israeli-built ‘Spike’ anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs) even as the DRDO is readying an indigenous man portable anti-tank guided missile (MPATGM) for the army.

A bulk of the current fast-track buys are for ammunition. The shortfalls, army officials say, have been caused by the Ordnance Factory Board (OFB), whose 41 factories have failed to keep the supply lines running. The OFB is part of the defence ministry’s Department of Defence Production. A series of Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) reports have highlighted deficiencies in OFB-produced ammunition. A 2015 CAG report noted that 74 per cent of 170 types of ammunition failed to meet the ‘minimum acceptable risk level’ and only 10 per cent met the ‘war wastage reserve’ requirements. Another CAG audit for 2017-18 presented in Parliament in December 2019 said that the ordnance factories ‘had achieved production targets for only 49 per cent of the items’. A significant quantity of the army’s demand for principal ammunition items remained outstanding as on March 31, 2018, adversely impacting its operational preparedness, said the report. OFB exports, the report said, decreased by 39 per cent in 2017-18 over 2016-17.

On May 16 this year, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced that the government was corporatising the OFB to improve ‘autonomy, accountability and efficiency in ordnance supplies’. Corporatisation, though, could take several years to bear fruit.

Attempts at private sector ammunition production have not taken off either, though not for want of capacity, capability or investments. In June, the army’s Master General of Ordnance Branch inexplicably pulled the plug on a 2016 plan to procure ammunition from the private sector. A brainchild of then defence minister Manohar Parrikar, the plan had aimed to bring the private sector into what was until then a government monopoly. It studied the 2016 experience where ammunition deficiencies led to fast-track buys. The goal was not only import substitution but also to create a vast domestic ammunition manufacturing capacity that the armed forces could tap into in an emergency. Deliveries would commence from six months of signing of the contract and spread over 10 years.

Fifteen private sector firms had planned to bid for eight procurement contracts for specialised tank, anti-aircraft and infantry ammunition for the army’s vast Russian-origin arsenal of battle tanks, anti-aircraft guns, multiple grenade launchers and 155 mm artillery guns (see A Lost Opportunity). Some of the private players had even established plants and scouted for international partners, anticipating orders. Five requests for proposal (RFPs) for ammunition were withdrawn while no decision has been taken on proposals for BMCS (Bi Modular Charge System) and fuses. With the collapse of long-term capability building plans, short-term weapons acquisitions will continue to remain more attractive.

No comments:

Post a Comment