India's Ocean, China's Sea

Building maritime muscle and projecting our reach in the Indo-Pacific should be a priority in India's plans to counter China's expansionism

by Admiral Arun Prakash (Retd) - Former Chief of Naval Staff

Historically, the maritime domain has played a crucial role in power transitions in India’s turbulent past, and since it will also be the source of future challenges, it continues to shape regional dynamics and our destiny. Unfortunately, maritime power has remained a ‘grey area’ for India’s political and national security elite, giving rise to the belief (commonly held by sailors) that they are afflicted with ‘sea blindness’. But is this an appropriate juncture to discuss maritime matters, when India is locked in a military confrontation with China on its northern borders?

While diplomatic and military parleys are under way, it appears unlikely that, given their past intransigence and exaggerated claims, the Chinese will pull back or agree to a settlement. Sino-Indian tensions are, therefore, likely to persist, and if India is not to cede ground, it will need to muster all elements, including the maritime, of its ‘comprehensive national power’ in order to negotiate from a position of strength.

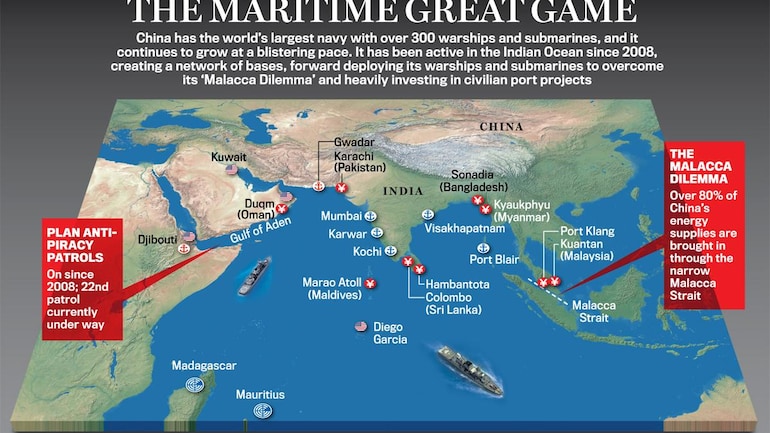

Given the Sino-Indian balance of forces on land, and the possibility of Sino-Pak collusion, it would be to China’s advantage to keep tensions confined to the Himalayas and to keep India contained in a ‘South Asia box’. All the more reason then for India to try and shift the confrontation to ‘sea level’, where the asymmetry is far in its favour. Way back in 2001, when India constituted the tri-service Andaman & Nicobar Command (ANC), it was perceived by Beijing as a move to dominate the Bay of Bengal and control the Malacca Strait. The ANC never rose to its potential, but such was its impact that in 2003 President Hu Jintao declared his apprehensions about “the Malacca dilemma” and called for mitigating strategies to protect China’s seaborne trade.

Hu’s forebodings have led not only to China acquiring ‘bases and places’ in the Indian Ocean littoral but also to the spectacular growth of the PLA Navy (PLAN). The past decade saw China adding two aircraft carriers, dozens of destroyers and frigates, along with amphibious shipping and tankers, to its large fleet of 70 nuclear and diesel submarines. This is a ‘blue-water’ navy designed for hegemonic projection of maritime power, and we may soon see a PLAN ‘Indian Ocean Squadron’ cruising our neighbourhood.

Since 1962, India has remained in a reactive mode to China’s steadily growing military pressure from the north. Coupled with naval pressure from the south, this could have ominous security implications, and calls for an agonising policy reappraisal in New Delhi. Fortunately, peninsular India dominates the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), highlighting the advantages of its ‘interior lines of communication’ as compared to 8,000-10,000-km-long ‘exterior lines’ that Chinese naval forces have to traverse.

Since the Indian Ocean sea lines of communication (SLOC) constitute China’s ‘economic jugular’, it is often suggested that India should threaten them. However, while ‘maritime blockades’ and interdiction of enemy shipping can be a productive wartime strategy, peacetime rules forbid interference with merchant shipping on the high seas. Trade warfare is a useful card to have up one’s sleeve, but it takes time to have an impact on the adversary. Since it is also a game that two can play, the Indian Navy’s operational philosophy is shaped around ‘sea control’ as the central concept, not only for protecting our own vital trade but also for enabling other naval missions like ‘sea denial’, ‘force projection’ and even anti-submarine warfare (ASW).

India’s 2015 Maritime Strategy, which lays down the operational actions required for maritime deterrence and/ or conflict, calls for a balanced fleet, comprising several aircraft carrier battle groups with integral multi-dimensional warfare capabilities. The 24x7 availability of a carrier’s air power at sea, which provides early warning, air defence, anti-ship and ASW capabilities, will be the critical factor that tilts the balance for an Indian force encountering PLAN intruders.

If the maritime domain remains hazy to most, its sub-set, maritime air power, is even less well understood and often gets shrouded in misconceptions. This has emerged in a recent media interaction, where the navy’s requirement for aircraft carriers was dismissed by a high defence functionary with the remark that“...since anything on the surface could be picked up by satellites and knocked off by missiles, the navy needs more submarines than aircraft carriers”. Critics of the carrier tend to focus on three aspects: its alleged vulnerability, its relevance in a changing battlespace and its cost.

The combat capability and survivability of a ship are functions of technology, intelligence and tactical acumen. China, in order to target US Navy carriers, has evolved an ‘anti-access area denial’ (A2AD) strategy, which relies on anti-ship ballistic missiles, amongst other measures, to target ships at long ranges. Once the initial panic had subsided, it emerged that a number of countermeasures, including anti-ballistic-missile missiles, directed-energy weapons and other hard-kill/ tactical measures were available to defeat this untried concept. Having conjured up the A2AD, China confounded everyone by embarking on an ambitious carrier-building programme of 6-7 ships; some, no doubt, destined for IOR deployment.

The carrier’s critics, fixated on its vulnerability, focus mainly on ‘hot war’ situations, forgetting that this platform has a huge peacetime role. Peace, which prevails 99 per cent of the time, is a clear indicator that deterrence is being maintained, largely by weapons systems like aircraft carriers. The carrier’s crucial contribution to upholding peace, without firing a shot, via functions like ‘presence’, ‘show of force’, ‘coercion’ and ‘compellence’ cannot be overlooked.

Also, it’s a misconception that a carrier needs to have an “armada for its own protection”. In most instances, the carrier actually provides it to other units in company through its resident air power, which endows it with unmatched reaction-speed, reach and flexibility. The carrier’s long build period enables its acquisition cost to be spread over many financial years. Practitioners of maritime power will always assert that regardless of cost, no combination of destroyers, frigates or attack submarines can substitute the carrier’s awesome combat power in war, or its impressive influence on sea during peace.

Xi Jinping has a clear-eyed vision of attaining his cherished ‘China dream’ via the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI). To meet the demands of the BRI’s ‘maritime Silk Road’ component, he has decreed a “world-class navy” for China, to enable projection of military power far from home. Time is running out for India, and it needs to craft a China-specific countervailing strategy, to safeguard its national interests. It is time to capitalise on our maritime geography and buttress our navy, while mobilising regional friends in the common cause of peace and tranquillity.

Strategic planners must bear in mind that it will not be its inventory of tanks or combat aircraft that make India an attractive partner for the US or the Quadrilateral and ASEAN. It will be India’s ability to project influence in distant reaches of the Indo-Pacific, via its maritime power.

No comments:

Post a Comment