Narendra Modi’s Military Purchases Remain A Pipe Dream For Lockheed, SAAB

A SAAB Gripen fighter of the Swedish Air Force

India’s inability to speed up the modernisation of its weaponry to guard the border with arch rivals Pakistan and China shows the Modi govt's challenge to transform an industry plagued by red tape. While New Delhi is the world’s fourth-biggest military spender, its air force, navy and the army are still equipped with weapons that are largely obsolete.

Global companies from Lockheed Martin to Sweden’s Saab AB are offering military hardware from submarines to helicopters to PM Narendra Modi’s government as part of his $250 billion defence modernisation program. But bureaucratic delays and a funding crunch has made future deals next to impossible.

Airbus SE won a $1.7 billion contract to supply transport planes to the Indian Air Force (IAF) in 2015 -- it’s first military agreement in the South Asian nation since 1962. Five years later, that deal is yet to be signed.

India’s inability to speed up the modernisation of its weaponry to guard the border with arch rivals Pakistan and China shows the Modi-led administration’s challenge to transform an industry plagued by red tape. While New Delhi is the world’s fourth-biggest military spender, its air force, navy and the army are still equipped with weapons that are largely obsolete.

“The defence procurement procedure needs major, thorough reforms, not just an update,” said Jon Grevatt, the Asia-Pacific defence industry analyst with Jane’s, adding the complex approval processes and lack of finances are the main drag on military modernisation. “Unless the Modi government really introduces major reforms into its procurement process then we will continue see delays.”

No Orders

An air of despondency hung over the gathering of top arms manufacturers last week in Lucknow, a nineteenth century battleground city in northern India. Executives heard Modi and Defence Minister Rajnath Singh extolling the need to modernise, collaborate and export out of India, while remaining silent on future orders.

A historic mandate about six years ago handed Modi a unique opportunity to aggressively buy arms, without fearing the political opposition that often derails such purchases. But implementation has been poor. The prime minister has missed that window of opportunity, at least seven executives said, asking not to be identified as they still do business with the government.

A Defence Ministry spokesman wasn’t immediately available to comment.

About 60% of defence spending goes to paying salaries for India’s 1.3 million soldiers -- one of the world’s largest standing armies. What’s left is spent on past purchases, leaving the forces with obsolete equipment and not enough ammunition.

India’s spending in the year starting April 1 will be $47.34 billion, of which $16.2 billion is for capital expenditure and of that, about 90% is devoted to existing obligations and committed liabilities. That leaves little to meet demands for weapons purchases and modernisation.

Time Lag

The political leadership is well aware of the need for modern weapons. The mainstay for Indian Army’s artillery are the Swedish-designed Bofors guns bought in the 1980s, while the air force and navy have an ageing fleet of Soviet-era aircraft and warships.

The process to buy fighter jets took more than a decade. What started as a requirement for 125 jets was pruned by two-thirds. When talks stalled over price and quality guarantees, the government scrapped the purchase in 2015 and bought 36 Rafale jets separately.

Aiming to develop a robust military industrial base, Modi’s government has revised defence procurement procedures, pushed for long-term strategic partnerships between Indian companies and global equipment manufacturers, further eased overseas investment regulations and diversified weapons suppliers.

Still, a parliamentary panel said implementation of the strategic partnership model which envisaged private players building military platforms like submarines and fighter jets in partnership with major global defence companies remains a non-starter. That’s mostly because of a lack of coordination in attracting foreign defence companies to set up local manufacturing, according to the 2018 report.

Technology Transfer

Saab AB pulled out of the race to locally build submarines after it realised it would have to assume all liabilities but wouldn’t have control over the venture. The company, which is pitching its Gripen jets to the government with billionaire Gautam Adani’s defence business, has now made clear it wants control of the venture if it’s required to transfer state-of-the-art technology to its local partner.

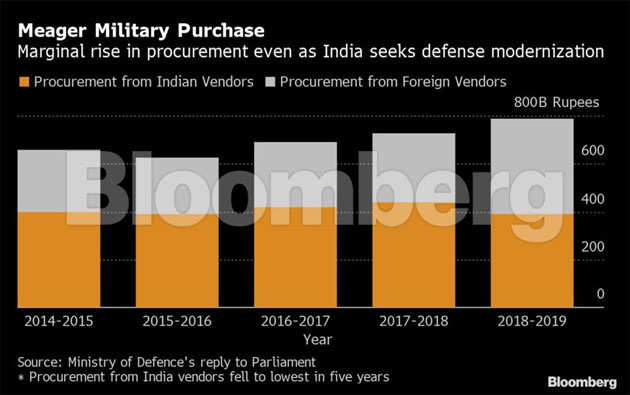

During the last three financial years till 2019, 149 capital acquisition contracts were signed and of these, 58 contracts worth about $20 billion were placed with foreign vendors, the defence ministry told parliament in December. These are small ticket items only, the company executives said, not submarines, jets or helicopters. Procurement from Indian vendors also fell to its lowest level in five years to financial year 2019.

“We are at least convinced that Saab and also other global original equipment manufacturers would be willing to transfer more technologies to India, if we have majority of control,” said Ola Rignell, chairman and managing director of the Saab India Technologies Pvt. Ltd.

No comments:

Post a Comment