Dalliance No More: How India-US Defence Trade Relationship Matures Over Years

The future of the India-US defence trade relationship will ultimately be tested against two touchstones: India’s continuing geopolitical promiscuity, and America’s zeal about guarding its technology

by Abhijnan Rej

On October 26, 1962, the Indian ambassador to the United States delivered a letter from his prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, to then US president John F Kennedy.

Six days before, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army had attacked India along multiple points on the boundary between the two countries. Nehru had asked Kennedy for American help in meeting this challenge (which was to become a complete debacle for India over the next month).

Kennedy obliged immediately. As historian Srinath Raghavan writes, “[w]ithin four days of the Indian request, the first American planes carrying light weapons landed in Calcutta. Over the following days, no fewer that forty-one aircraft carrying over 40,000 tons of equipment touched down in India.”

This could have been the harbinger of a much closer US-India defence relationship had New Delhi’s stubborn and vocal commitment to ideology (non-alignment), Washington’s apathy towards India (again, but only, because of non-alignment) and Pakistan’s perfidy (resulting in war three years later) not gotten in the way.

It had to wait almost another four decades before the United States finally committed to the idea of a strong India as an intrinsic good, and the Indian strategic elite (mostly) shed its instinctive anti-Americanism.

Since the early 2000s, the United States has emerged as one of the most important military partners for India, rivalling only Russia in its net importance. It has sold India naval surveillance aircraft that allows the Indian Navy to manage the threat of Chinese submarines in its backyard, supplied India with turboprop military transport aircrafts and attack helicopters, and approved the sale of sophisticated naval guns, among many other items.

In the words of a scholar from a famous European think-tank, “India is now at that level where it’s basically like a NATO partner even if there’s no alliance.” What is all the more remarkable is that the US-Indian defence relationship, including arms trade, has continued to flourish despite many persistent political and economic points of friction.

The following is a story of the US-India military trade relationship, told through key statistics. (An accompanying note describes the data sources and methodology used in this article.)

The United States sells arms to other countries through two different routes. The first one is that of Foreign Military Sales (FMS) – essentially a way through which the US government itself procures the weapons system from an American military contractor and then sells it to a state after charging a mark-up cost (3.8% of the price in case of India).

It has been argued that the FMS route has been extremely useful in the past given the sclerotic nature of India’s defence acquisition process, though its principal weakness – as IDSA’s Laxman Behera has pointed out – lies in the onerous end-user monitoring conditions that comes from a government-to-government sale.

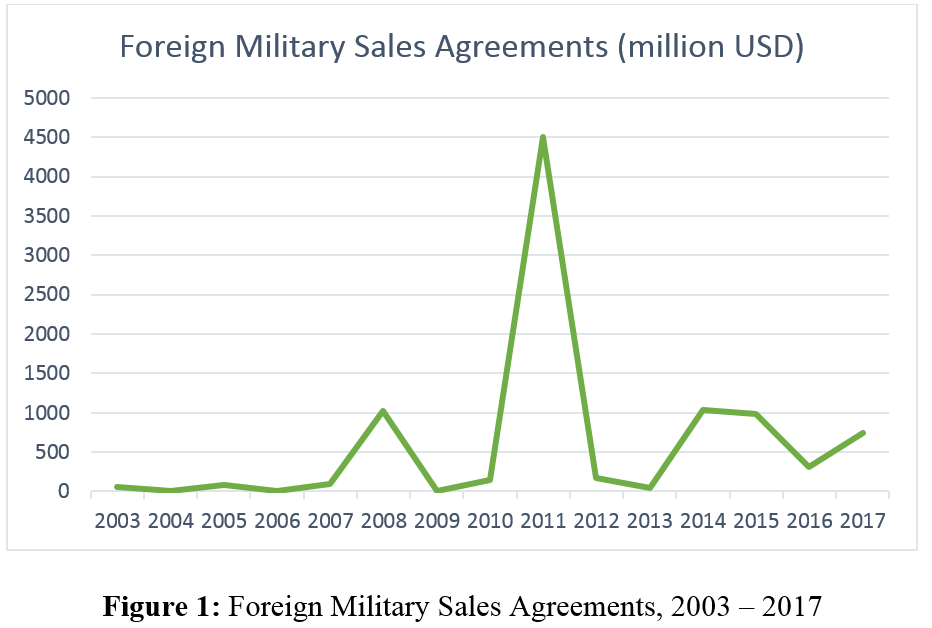

Between 2003 and 2017, the US entered into a total of around 9.2 billion dollars of agreement to sell military hardware to India through the FMS mode, with agreements peaking at 2011, at 4.5 billion dollars (see Figure 1).

A 2019 State Department statement notes the FMS route has been used to sell India “MH-60R Seahawk helicopters ($2.6 billion), Apache helicopters ($2.3 billion), P-8I maritime patrol aircraft ($3 billion), and M777 howitzers ($737 million).”

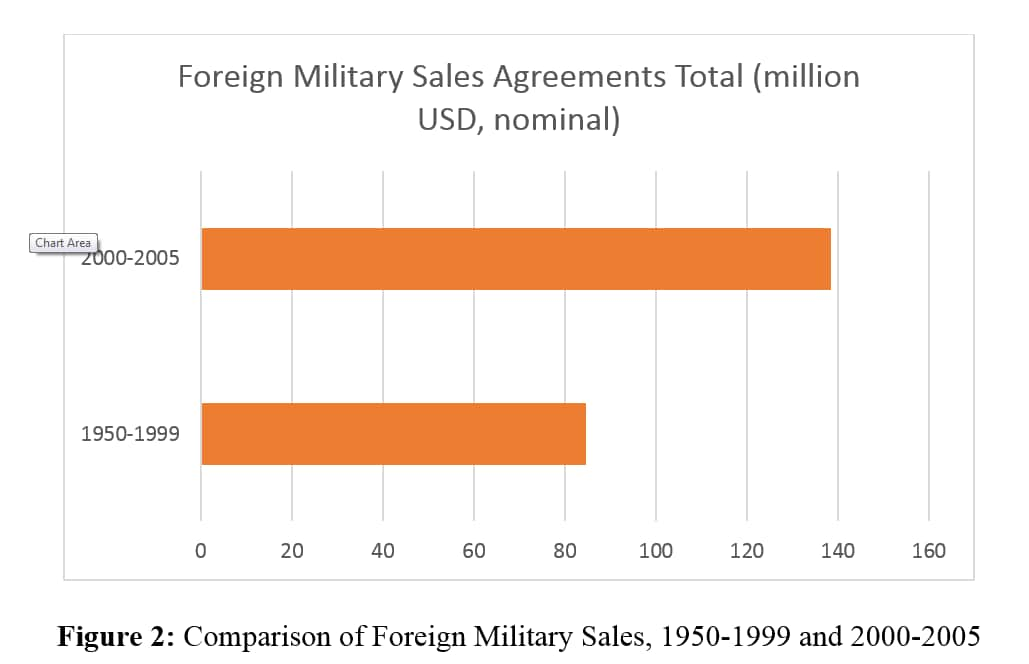

To see how spectacular this growth has been, note that between 1950 and 1999, FMS agreements between the US and India amounted to a total of about 85 million dollars – a reflection of how weak the defence trade relationship between the two countries were after the brief dalliance during the 1962 war.

While the US (along with other western countries) refused to sell India weapons after the 1965 war with Pakistan – note that during the Cold War, Pakistan was a frontline ally of the United States, leveraging its geography as the West fretted about a Soviet ingress into Afghanistan – the Soviet Union itself provided to be all too obliging in this regard, offering concessions and “political prices” for its equipment.

With the end of the Cold War and dissolution of the USSR, in 1991, India found itself in dire straits when it came to sourcing military hardware. It is only around the turn of the new millennium that the US emerged as a natural choice for India when it came to defence trade, even though Russia continued to be India’s leading defence partner.

India’s diversification of its defence relationships to include the US was undoubtedly the result of what can be called the pragmatic turn in Indian grand strategy beginning with Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s vigorous outreach to Washington.

The Indian overture was effectively consolidated by emerging geostrategic reality – marked by dramatic attacks on the American homeland in September 2001 as well as growing awareness about rising China’s ambitions – as the Bush Administration perceived it.

The end-effect of this surprising alignment on the US-India defence trade relationship was spectacular. In the three years – between 2003 and 2005 – FMS agreements volume grew to more than 138 million dollars. (See Figure 2 though do note that not all agreements end up in completed sales. Also note that the comparative figures are in somewhat-misleading nominal terms that do not take inflation into account.)

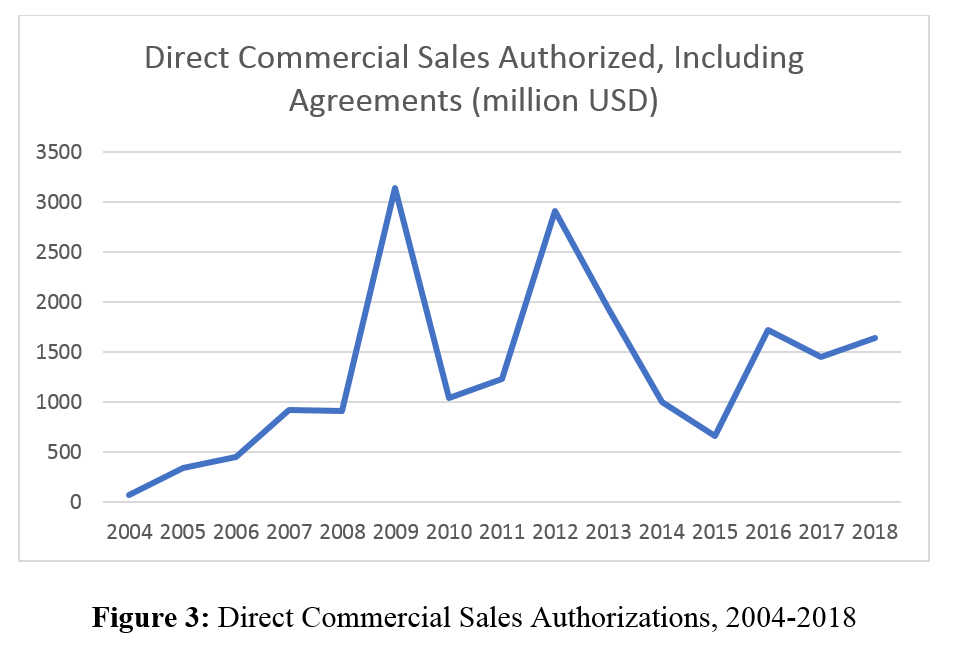

If government-to-government weapons sales are one way through which the US sells weapons to India, the Direct Commercial Sales (DCS) route is the other. Through the DCS mode, the Government of India directly buys weapons from US military contractors subject to the approval of the US Congress in some instances and mandatory State Department authorisation that grants the contractor the license to sell weapons or even enter into arms sales agreements.

This has been historically the most cumbersome method through which India has procured American weapons, largely due to problems with the Indian defence acquisition process. That said, the United States’ political commitment to selling India high-technology weapons can be gleaned through the volume of DCS it has authorized, totalling to about 19.5 billion dollars till 2018 (see Figure 3).

Since 2008 India has purchased 6.6 billion dollars’ worth of American military hardware – including aircraft, electronics, and gas turbine engines – through direct transactions with American companies.

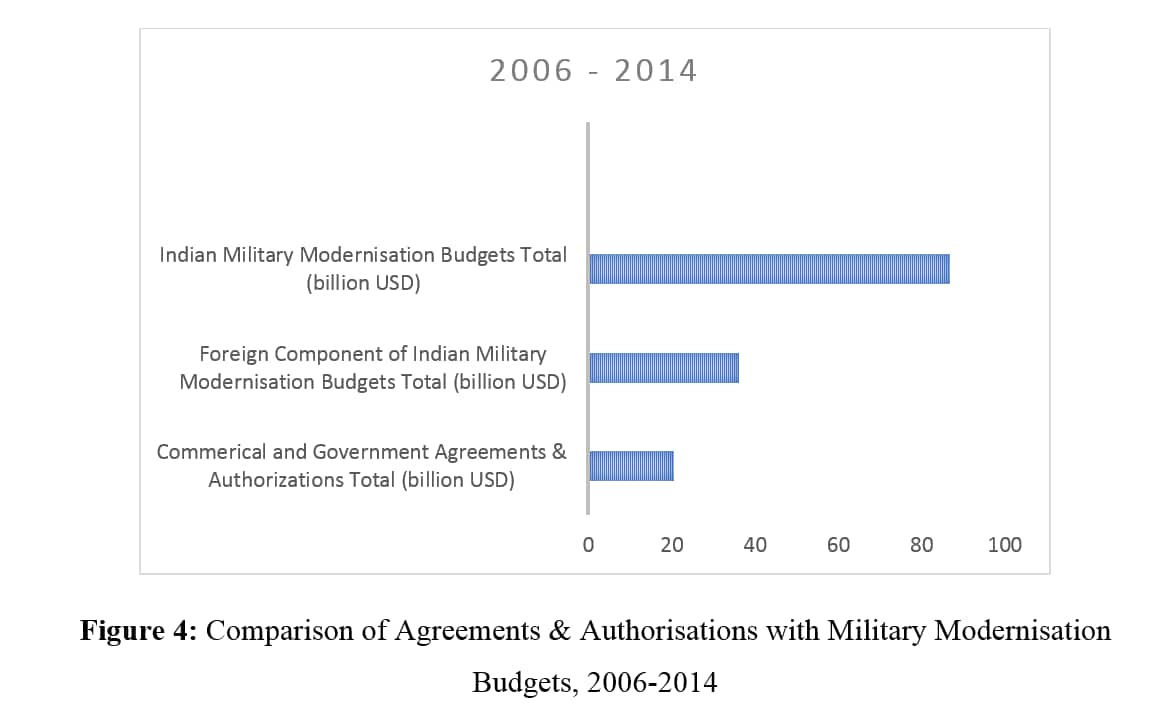

There are two obvious problems with measuring the quantum of American “claim” to India’s military modernisation budget. First, not all agreements and authorisations from the American end results in purchases and transfers, and second, even the ones that do spread over several budgets in terms of financial commitment and liability, and delivery often happens many years after the agreement was inked.

Put differently, if India was to sign an agreement to buy item X tomorrow from the US – and assume that Washington green-lighted the sale – significant time would pass between tomorrow and the day the weapons system arrives on India’s shore. That said, one can use the proxy of volumes of US arms authorisations and agreements to gauge the depth of the US-India defence trade relationship (see Figure 4).

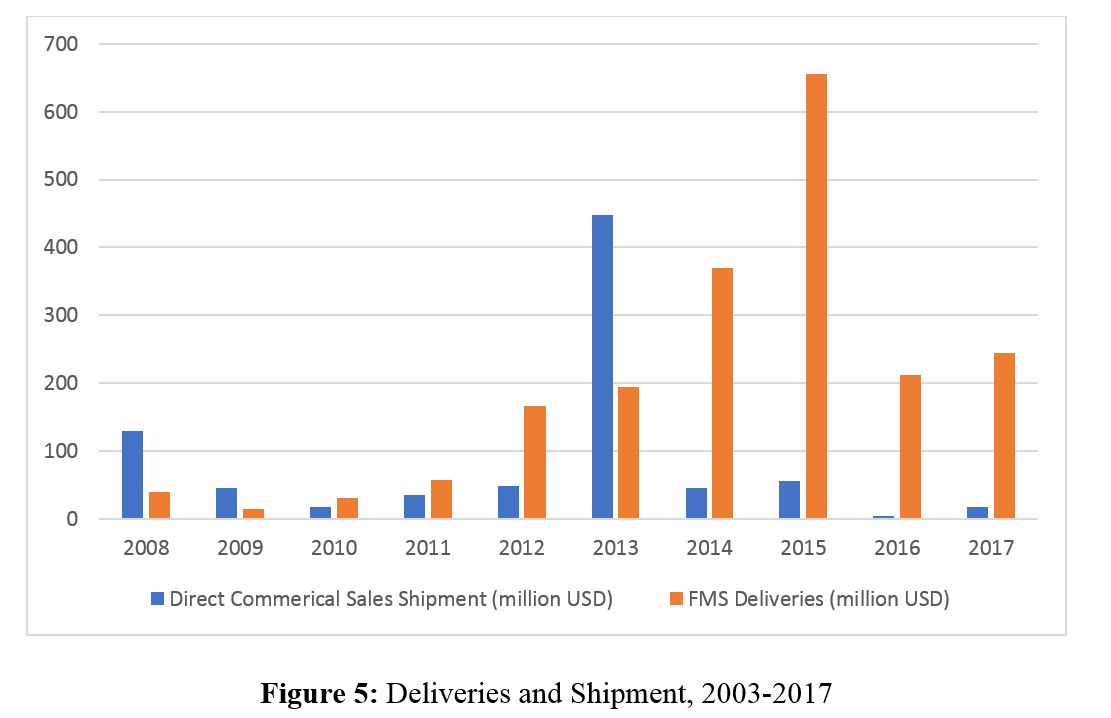

That said, one can estimate the dollar amount of US weapons already delivered to India: between 2008 and 2017, India received 2.8 billion dollars of US military hardware. What is interesting about the pattern of deliveries in this time period (Figure 5) is that the FMS route has led to the most deliveries, more than 2.3 times the DCS route.

This is consistent with what most Indian defence analysts know: the DCS route so far has proved to be sub-optimal in procuring American weapons despite the end-use flexibility it may offer.

The future of the India-US defence trade relationship will ultimately be tested against two touchstones: India’s continuing geopolitical promiscuity, and America’s zeal about guarding its technology. Already it is clear that should India accept the delivery of the Russian S-400 Triumf anti-aircraft missile batteries, the United States (especially its air force) will be extremely reluctant to allow India advanced American fighter jets. At the same time, sections of the Indian strategic community have noted the fundamental American reluctance to part with technology that India needs the most to develop its indigenous defence base, say that for jet engines.

But as Donald Trump lands here next week, both Indians and Americans would be well-advised to once again revisit the long road the defence relationship their two countries have traversed over the years by way of inspiration.

The author is a New Delhi-based defence analyst and researcher. Views expressed are personal

No comments:

Post a Comment