Missing Teeth

A CGI rendering of INS ARIHANT firing a K-5 SLBM

by Pradip R Sagar & R Prasannan

WHICH SHOULD come first? The weapon, or the drill for using it? Most warriors would say the weapon should come first. Indian defence planners, however, do not seem to agree.

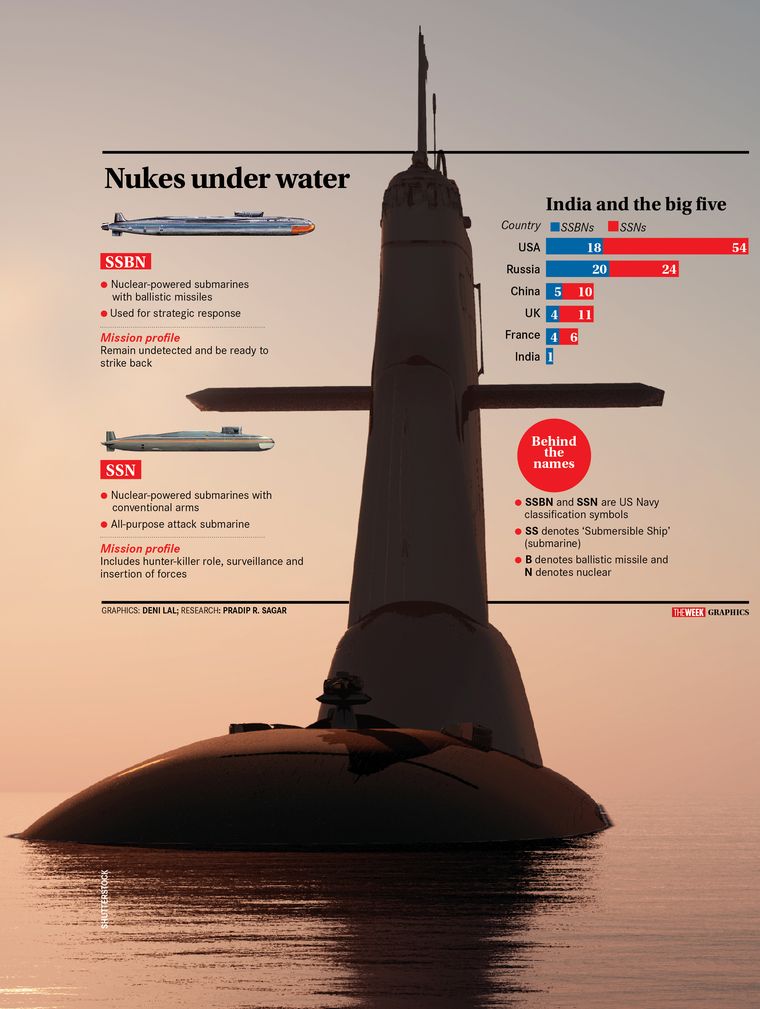

Similarly, what should come first? Nuclear-powered submarines with conventional arms (SSNs), or nuclear-powered submarines with ballistic nuclear missiles (SSBNs)? The world’s big five went for SSNs first, and SSBNs next. Again, India bucked the trend.

India’s nuclear ‘drill’, or the doctrine for induction of nuclear weapons, was made way back in 1999, a year after India declared that it had made the bomb. In August 1999, in the middle of a general election campaign, national security adviser Brajesh Mishra unveiled a draft doctrine which declared that India will not use its bombs unless the enemy hits India with bombs.

The doctrine also clarified that India would have a triad of weapons to activate the doctrine—squadrons of bomber planes, nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles and nuclear-powered submarines for carrying nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles.

The logic of deterrence is as old as the Cold War. An enemy who makes a first strike would target India’s bomber squadrons and missile batteries first; since nuclear submarines remain under water, they would have better chances of survival, and would be available for a hit back. As long as the enemy knows that India has a few such missile-armed boats that cannot be located and destroyed, he would not risk a first strike on India. So, “SSBNs are not meant for fighting wars, they are to prevent wars,” said Vice Admiral A.K. Singh (retd), who had commanded India’s first SSN, INS Chakra, taken on lease from Russia. “Nobody will attack you if you have an SSBN.”

The first two arms of the triad had already been in place when Mishra unveiled the doctrine. India already had squadrons of Sukhoi-30MKIs, Mirage 2000s and Jaguars, which could drop bombs on enemy targets. India also had a few batteries of Agni missiles with nuclear tips.

But, the third, the SSBN, took 19 more years. Finally, on the eve of Diwali, the secret boat crew led by Captain Mukul Suranghe called on Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who carries the nuclear button, saluted him, and formally told him that their trials were complete and the boat was ready to serve the nation.

Dedicating the boat to the nation as a Diwali gift, Modi said: “Arihant is an open warning to enemies of India and enemies of peace” and a “fitting response to nuclear blackmail”. With that, India joined another club where the same big five— the US, Russia, Britain, France and China—have been sitting.

INS Arihant, an SSBN category submarine, is both nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed. She is armed with 750 km range K15 Sagarika nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles. In future, she will get 3,500 km (intermediate range) K4 ballistic missiles.

A sister ship is getting ready in the Navy’s secret yard at Visakhapatnam. There will be follow-on ships, all of which will move around the depths of the waters close to China’s and Pakistan’s coast. At least six have been planned and two are learnt to be in the works.

“The initial plan was to have six Arihant class submarines, but now, another three have been added, which would be with upgraded specifications,” said an officer at the naval headquarters. “Two would be much bigger in size to accommodate more advanced weapons. We need larger submarines than Arihant, which is about 12,000-13,000 tonnes, since we will soon have longer-range missiles. We require at least four to have 24x7 deterrence,” he said.

But the Navy’s fleet of attack submarines, all diesel-powered, has dwindled from an awesome 21 in the 1980s to just 14 at present. Worse still, at least half of the 14 available boats are old and creaking, and undergoing mid-life upgrade. It means India has just seven submarines that are battle-ready at any given time, against 65 of the Chinese navy.

Ideally, the Navy needs at least 24 submarines to meet its 30-year submarine building plan, which was approved by the cabinet committee on security in 1999, months after the Kargil conflict. The plan was to induct 12 diesel subs by 2012 and another 12 submarines by 2030, but repeated delays forced the Navy to rejig the plan. Now, the plan is to have 18 diesel-powered submarines and six SSNs. The SSNs will be constructed in Visakhapatnam. Meanwhile, to develop skills and drills for operating SSNs, the Navy has got one Akula-class SSN on lease from Russia.

The main underwater fighting will have to be done by SSNs, but India has none of them. That leaves India in a strange position—a nuclear power which has deterrence capability with at least one SSBN, but has no nuclear-powered attack submarine or SSN, the type that can be used in actual underwater combat.

The gap will take another ten years to be filled. Early this year, the cabinet committee on security approved a programme to build six nuclear-powered attack submarines, costing an estimated Rs90,000 crore. “The project to build six nuclear attack submarines has taken off,” Chief of the Naval Staff Admiral Sunil Lanba told THE WEEK. “But it will take at least a decade to complete.”

The six SSNs are billed as India’s only answer to Beijing’s naval might in the region, which is increasing with the building of a deep sea port on the western coast of Myanmar’s Rakhine state. It is too close for comfort for the Indian Navy, which has its submarine base in Visakhapatnam. The move is perceived as part of the ‘string of pearls’ effort to encircle India, after the Gwadar port in Pakistan and Hambantota in Sri Lanka.

Admiral Singh, however, said six SSNs would not be enough. “We need at least eight. We are way behind the Chinese. They have been making SSNs since 1976. They have ten SSNs and five SSBNs already.” SSNs, which are armed with conventional weapons, are stealthier than diesel subs. Their engines make less noise and thus are less likely to be picked up by enemy subs. Second, diesel subs can be spotted by enemy aircraft as they have to surface every day or every other day to take in oxygen for recharging their batteries. SSNs can remain under water for months at a stretch.

According to Admiral Singh, an SSN is like a fighter jet, which can be launched for long-range combat patrols. “SSN is for fighting wars, unlike SSBNs which are for deterrence,” he said. “One SSN can create enormous threat in the South China Sea and East China Sea and all around the Chinese coast. Similarly, one Chinese SSN can create enormous threat in the Indian Ocean region.” It can rapidly accelerate and decelerate, and can perform multiple combat tasks. “It can shadow enemy ships by staying deep, and can launch attacks. It is also employed for defending carrier battle groups,” he said. The Navy is planning to have three carrier groups, which means three of the six SSNs would be employed in escorting them.

All the same, everyone agrees that Arihant is a milestone, and it is a strategic deterrent. “Nuclear weapons will never be used, but to ensure that it is not used, you require to have conventional capability,” said Vice Admiral (retd) Shekhar Singh, who headed the western naval command. “India is the only country which has developed an SSBN, but hasn’t built an SSN.”

No comments:

Post a Comment