There Is Growing Civil-Military Dissonance And Acrimony In India’s Defence Ministry

The Indian military needs to introspect and ensure that no one has the cause to cast aspersions on its personnel

by Arun Prakash

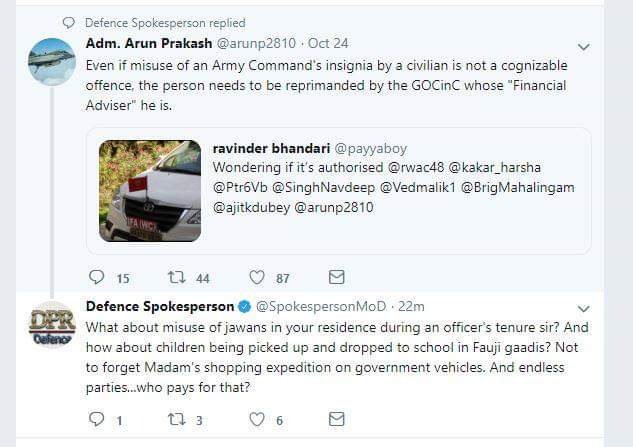

The Twitter episode involving the ministry of defence spokesperson’s outburst this week has revealed deep tensions in India’s civil-military relations.

When it was pointed out that a civilian officer’s car should not have a military flag on the bonnet, the ministry of defence spokesperson retorted by listing the privileges that are allegedly misused by military officers.

But the real problem is that the Indian military space, within the national security arena, has been progressively dwindling since Independence and the process continues even today.

The ministry of defence is manned and run exclusively by civilians, but the recent constitution of the Defence Planning Committee and re-organisation of the Strategic Policy Group further marginalises the military. A million-strong ‘armed police force’ has been created; whose officers wearing military rank-badges and constables clad in camouflaged combat-fatigues make it look like a ‘rival’ army. Thus, army units that render aid to civil power, feel obliged to carry large placards reading ‘ARMY’ to distinguish themselves from look-alike policemen.

Army units that render aid to civil power, feel obliged to carry large placards reading ‘ARMY’ to distinguish themselves from look-alike policemen

But the real crunch lies elsewhere. Pursuant to the recommendations of the Group of Ministers after Kargil, certain financial powers were ‘delegated’ to senior military functionaries so that they could meet essential revenue expenditure without delay. Within a few years, the defence finance bureaucracy struck back, and imposed severe curbs on these powers. A cadre of ‘Integrated Financial Advisers’ (IFA) was created to staff each financial authority.

Thereafter, no military authority, from vice chiefs downwards, could exercise delegated powers without written ‘concurrence’ of the IFA. With notable exceptions, IFAs have forgotten their ‘adviser’ function and have assumed the role of ‘auditors’; they lie in ambush, often delaying cases of urgent operational nature on specious grounds.

For example, a C-in-C wanting to replace a submarine’s batteries or have a harbour dredged may be kept waiting for months, as the IFA seeks successive ‘clarifications’ and after which, may or may not accord concurrence. In the interim, if the submarine has a mishap, or a ship runs aground, the C-in-C’s head will roll, but the IFA will not be accountable.

Is it the propensity of few IFAs to delay or impede the acquisition of operational capabilities that prompts military formations to accord them VIP status and special privileges? Does it, then, explain why one of them felt entitled to fly a military flag on his vehicle as seen on social media last week. On the flip side, there is also a need to question how well the military assimilates the IFAs, deputed to serve in an unfamiliar environment. Rather than treat them as VIPs, it would be far better to make them feel at home and convert them into ‘team players’, without diluting their fiduciary functions.

Against this background, Friday’s tweet by the MoD spokesperson, and the furore that followed, was a ‘storm in a teacup’ because the tweet was declared ‘inadvertent’ and promptly withdrawn.

However, it did serve a purpose by focusing on two important and worrisome issues that demand attention.

First, the civil-military relationship (CMR) in India seems to have acquired a bitter edge. CMR is an area with serious implications for national security, but whose crucial significance seems to have eluded India’s post-Independence rulers. A key feature of the current state of CMR is the perceptional gap that exists between the two sides. On one hand, the politico-bureaucratic establishment sees nothing amiss and remains a staunch upholder of the ‘status quo’. On the other hand, the military is deeply dissatisfied with the growing asymmetry compared to the bureaucracy and police, wrought via successive pay commission awards, but is powerless to stem the decline.

The bureaucracy, by resisting the integration of service headquarters with the ministry of defence, has not only denied this ministry badly-needed professional expertise and decision-making ability, but also the synergy, economy and efficiency that would have come with such assimilation. Instead, there is growing civil-military dissonance as well as mutual acrimony in the defence ministry, which does not bode well for its functioning.

The Friday tweet was an indicator of the underlying rancour. Using instinctive ‘what-aboutery’, the spokesperson mentioned misuse of service personnel and transport as well as entertainment at government expense by military officers. Even though the tweet was removed and the official replaced, these allegations, aired by an IDAS officer, need to be noted.

This brings me to the second issue.

India’s armed forces have traditionally stood tall above civil society, and been held in respect and admiration. Today, if they seem to be slipping in the estimation of their countrymen, we need to search for the reason why. Some may try to rationalise this by saying that the soldier is a product of Indian society and his/her conduct is bound to reflect societal decline. There could also be a persuasive argument that says, “But everyone in India misuses Sarkari facilities; why not us?”

The seductive comfort of such logic must be firmly rejected. Apart from being guardians of the nation’s security, and the embodiment of order and discipline, the military must remain an exemplar of honourable and ethical conduct. Soldiers have always lived (and died) by a ‘code of conduct’ several cuts above the one prevailing in civil society. As institutions all-around, crumble, the military needs to introspect deeply and ensure that no one, ever, has cause to cast aspersions of this nature on its personnel.

The author is former Indian Navy Chief

No comments:

Post a Comment