A new generation of air-to-air missiles is set to transform the Indian Air Force’s fighter fleet

by Mihir Shah

It has been an exciting two years for India’s air-to-air missile program. After years of making do with obsolescent weaponry, the Air Force’s fighter squadrons are finally set to equip themselves with an arsenal of cutting-edge missiles. The Astra missile

recently entered limited production; the European ASRAAM is on the verge of

being adopted as the standard close-combat missile; a high-tech long-range missile is being acquired to arm the Rafale multi-role fighter; and another homegrown long-range missile

has undergone two successful trials.

This article appeared in March 2019

Here is why the developments on the horizon represent a generational leap in the capabilities of the Indian Air Force.

Missiles have Displaced Guns As The Primary Air Combat Weapon

Classical aerial gunfights are rare in modern times. A contest whose outcome hinged on pilot skills and aircraft agility is now dominated by battlefield transparency, sensor technology, and air-to-air missiles (AAMs) that can hit enemy aircraft at extended ranges.

Early missiles—like the American AIM-9 ‘Sidewinder’ and the Soviet K-13—offered a crucial advantage over guns and cannon. They could latch on to enemy aircraft using infrared seekers and autonomously ‘guide’ themselves towards their targets. But they had short legs, exhibited poor performance in the field, and accounted for a tiny fraction of air combat ‘kills’.

But as technical development continued at a rapid pace, the picture changed. Heat seeking missiles became more accurate, and a new generation of radar-guided missiles offered the ability to hit targets at extended ranges. By the dawn of the new century, missiles had come to claim more than 95% of all aerial kills, more than half of which were credited to the so-called Beyond Visual Range Air-to-Air Missile (BVRAAM).

The Indian Air Force itself had a glimpse of the overpowering advantage that BVRAAMs enjoy during the Kargil War of 1999. There was at least once instance when Indian MiG-29s, armed with medium-range missiles, obtained radar lock on Pakistani F-16s far across the Line of Control. The F-16s were only equipped with short-range Sidewinder missiles, and quickly turned tail. Throughout the war, the presence of the MiG-29s would give Indian strike aircraft complete freedom of action over Kargil, and allow them to bomb enemy positions with relative impunity.

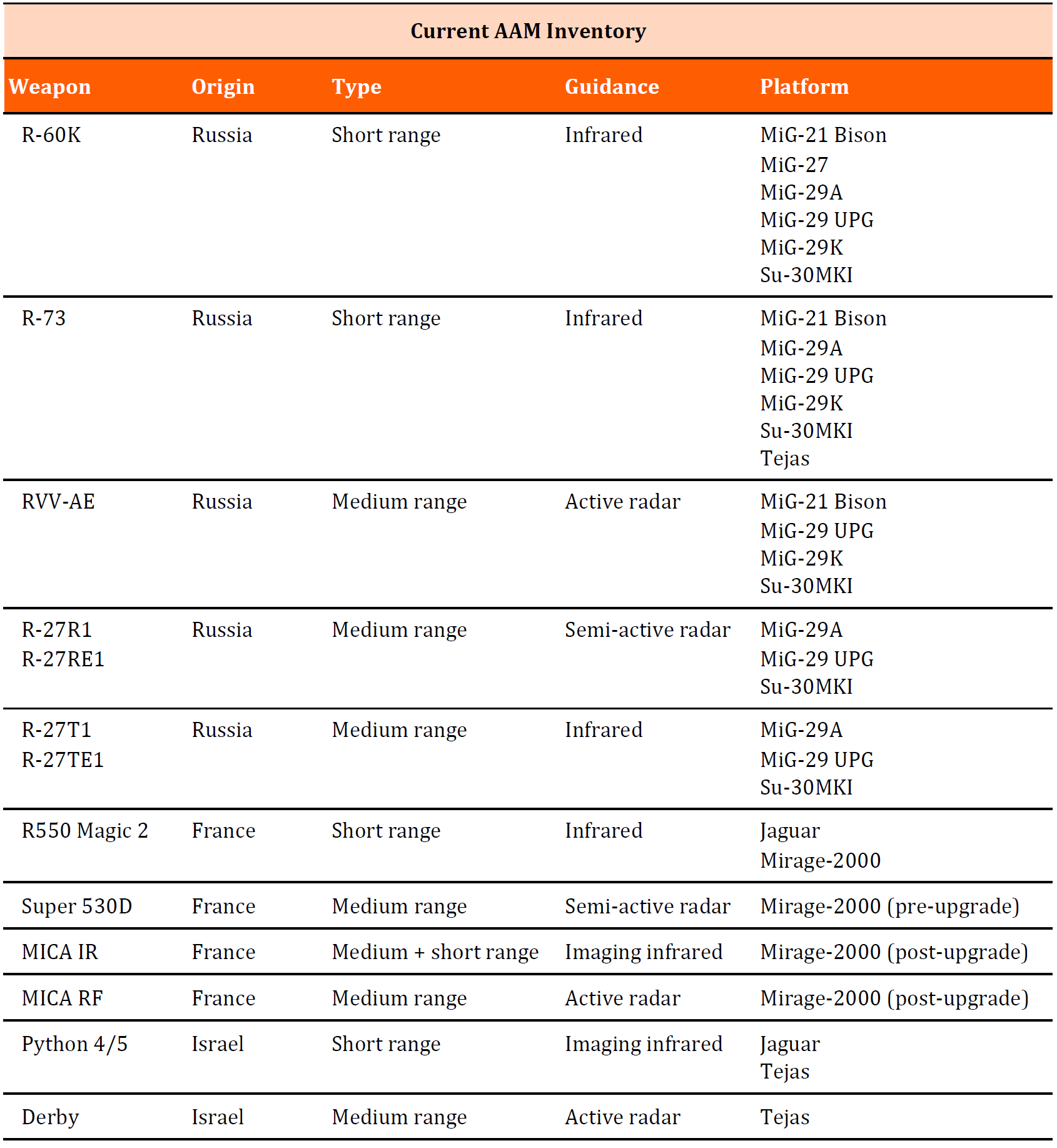

India’s Legacy AAM Inventory Is No Longer Up to Snuff

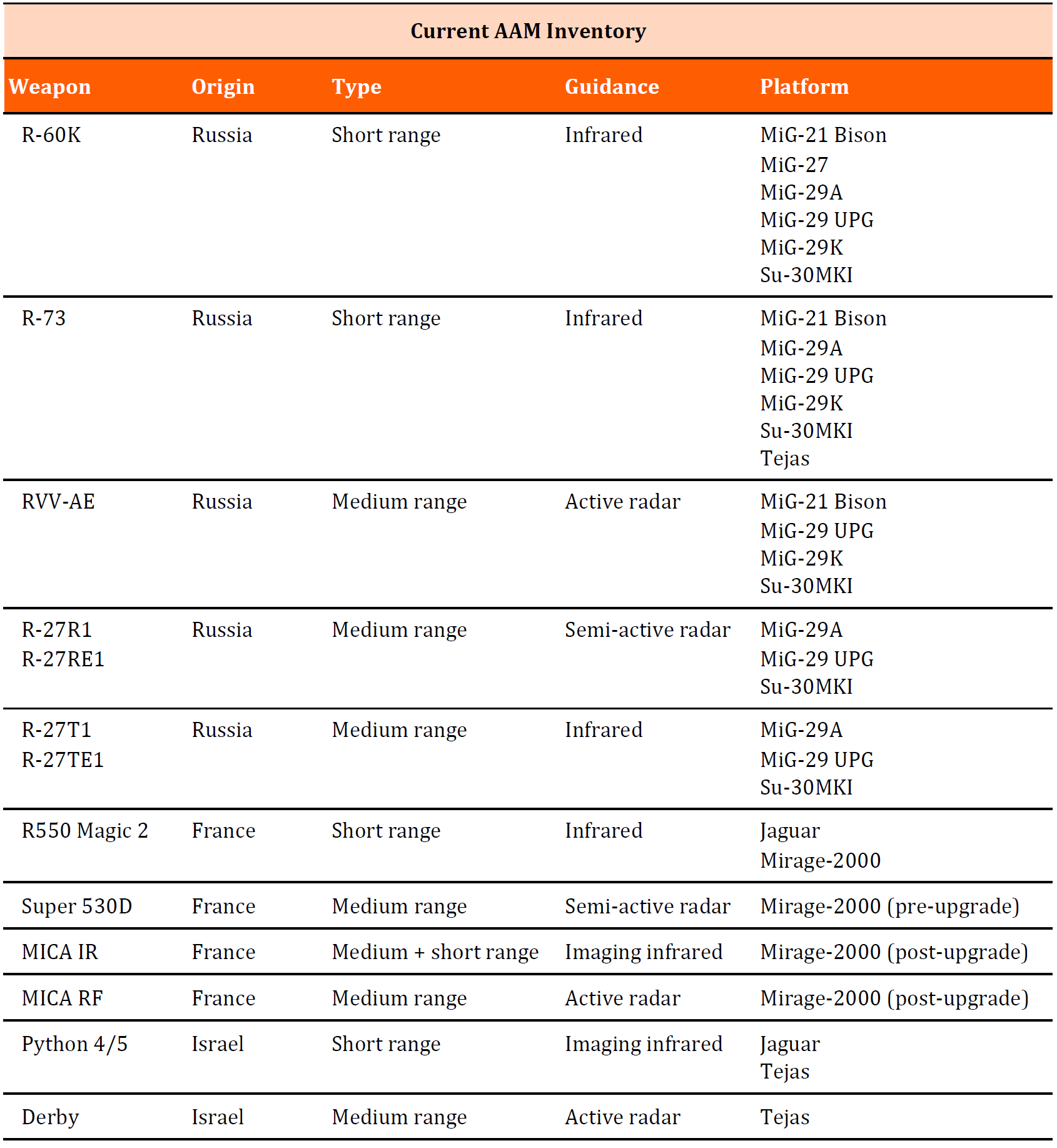

Today, much of India’s AAM arsenal is starting to look outdated, and the ascendancy that the Air Force demonstrated in Kargil has begun to erode.

Of the current crop of close-combat missiles (CCMs), the R-60K and Magic 2 are wholly outdated. The R-73, while still capable, is being outperformed by newer missiles like the Israeli Python, American AIM-9X, and European ASRAAM. The MICA IR fulfills a dual role as a medium as well as short-range missile, but equips only the Mirage-2000 fleet. And while the Python has been cleared for carriage aboard the Tejas LCA, there has been very little movement on bulk orders, making their future in the IAF far from certain.

The circumstances are no different with the arsenal of medium-range missiles, of which only the MICA and Derby may be described as modern. These equip only a small fraction of the fighter fleet, with very little ability to interface with IAF’s frontline fleet of Su-30MKI air dominance fighters.

The RVV-AE too is nearing obsolescence—the variant that equips the Indian Air Force has a design that dates back to the early 1990s. The missiles were ordered to equip the Air Force’s fleet of Russian fighters starting 1996, and for a time, they gave it a significant edge over Pakistan. However, they proved difficult to integrate with the MiG-21 Bison, were

plagued with serviceability issues, and the initial batch reached the end of its service life before the problems could be resolved. While there are unconfirmed reports that the Defence Ministry under Manohar Parrikar led an aggressive effort to fix the defects in rest of the inventory, it is hard to gauge whether these moves were successful.

If the RVV-AE is aged, then the R-27 (in all its variants) and Super 530D are positively antiquated, their semi-active guidance mechanism making their employment unwieldy and exposing the launch platform to serious risk. The former is deployed on the Su-30MKI for lack of a viable alternative; and the latter is being phased out as the Mirage-2000 fleet is upgraded.

Even as India struggles to fight the creeping obsolescence within her AAM inventory, Pakistan and China have built up large stockpiles of modern missiles. Pakistan started equipping its fleet of F-16 fighters with the battle-proven AIM-120C5 medium-range missile in 2010,

while China adopted a homegrown weapon based on the RVV-AE in 2006-07. China has also showcased a clutch of

close-combat and

long-range missiles more recently, although induction timelines remain opaque as ever.

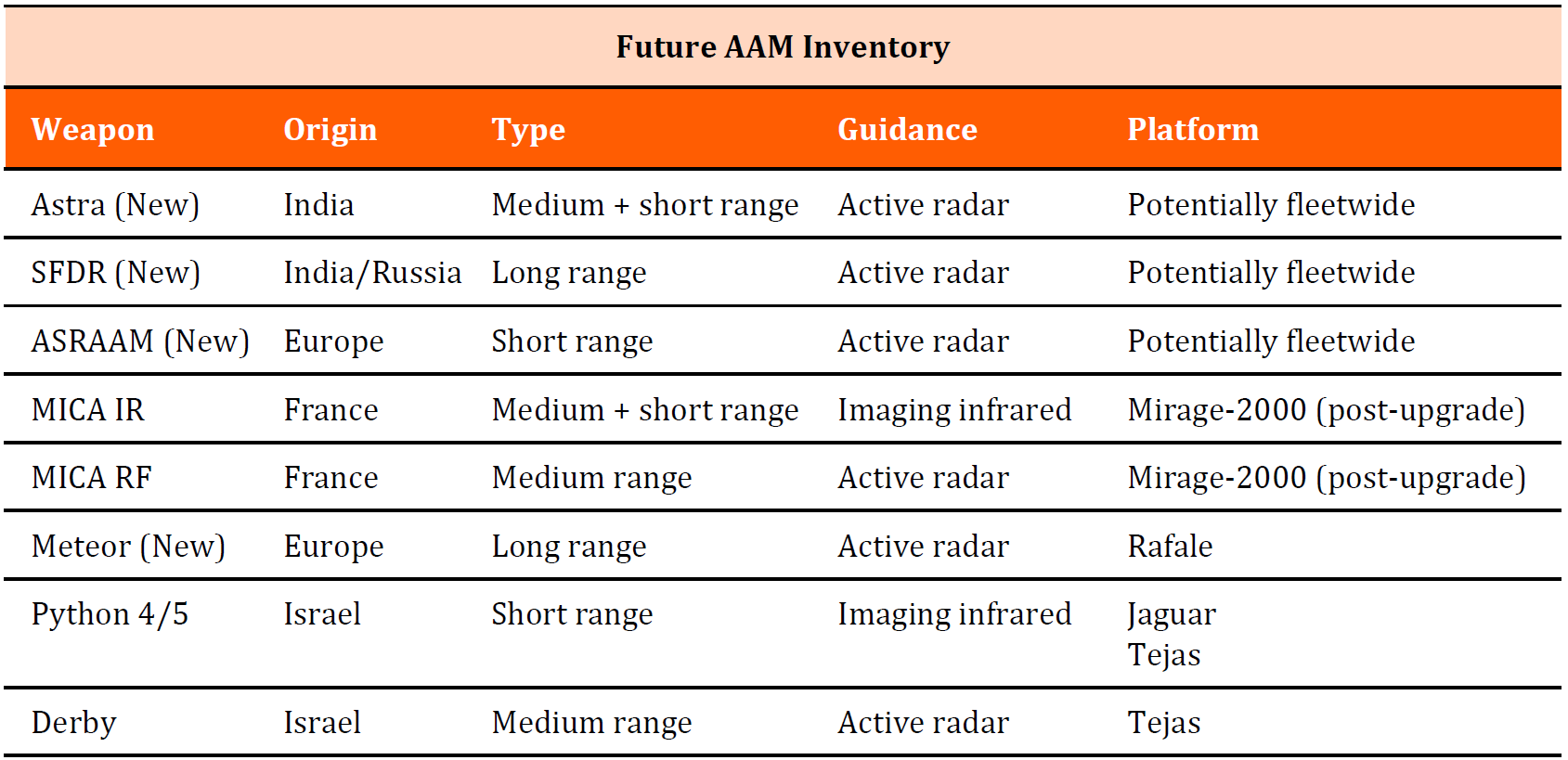

A New Generation of Missiles are About to Replace This Legacy Arsenal

In the near-to-mid future, we are likely to see India’s AAM inventory modernise again. Many of the legacy CCMs will potentially be replaced with the

highly-capable MBDA ASRAAM. Its agile airframe, coupled to an imaging infrared seeker that offers increased accuracy over older infrared seekers, makes for a lethal combination in aerial dogfights. Moreover, the manufacturer’s proposal to

locally produce the ASRAAM in Hyderabad represents the cherry atop the proverbial icing. If the Ministry of Defence gives its green light to the proposal, the economies generated via adoption at scale as well as domestic manufacture ought to make an already attractive prospect even more appealing.

A surprise spotlight landed on the ageing R-73 last month when an Indian Air Force MiG-21 Bison is claimed to have shot down an aggressing Pakistan Air Force fighter using the close combat missile. Russia’s Tactical Missile Corporation JSC, which administers the R-73’s developer Vympel NPO, has been energised by the incident and is likely ride out the attention with fresh offers of its improved air-to-air missile family, including the RVV-MD close combat, RVV-SD medium range and RVV-BD beyond visual range missiles. India’s interest in buying 21 more MiG-29s, 18 more Su-30 MKIs and standing bids for the MiG-35 and Su-35 mean the Vympel family almost definitely have place in India’s future missile arsenal.

At the same time, the

indigenously developed Astra (in its current and future variants) will replace all the Russian-origin BVRAAMs, and likely supplement the MICA and Derby missiles that arm the Mirage-2000 and Tejas squadrons.

This no doubt comes as good news for an Air Force that is

battling simultaneous shortages in several areas. The Astra, in particular, represents a major shot in the arm. It boasts a host of modern capabilities such as a sophisticated radar seeker, the ability to defeat electronic counter measures, smokeless propellant (which makes it challenging for an enemy aircraft to spot the shooter), a directional warhead (which improves its chances of destroying an enemy aircraft), and more. It also offers an assortment of launch and guidance modes that allow it to be used across a wide variety of engagement scenarios. And like the French MICA, it can also double up as a close-combat missile, launching hot off the rails to attack enemy aircraft at short ranges.

Besides, the Astra offers advantages that extend well beyond the raw capabilities of the missile itself. Because the missile has been designed and manufactured in India, it reduces the nation’s vulnerability to technology embargoes from abroad. Since it has an Indian seeker, its electronic secrets remain hidden from adversaries, making it difficult for them to develop counter-measures. And as a result of the intellectual property being owned by Indian entities, developing follow-on variants would not require approval from foreign entities. It would also be less challenging to interface with the IAF’s fleet of Tejas, MiG-29 UPG, Mirage-2000, and Rafale fighters. The availability of rounds for training and familiarisation would also be an advantage. BVR missiles are currently seen as scarce resources; meant to be carefully stockpiled and used only against high-value targets in war. Now with these missiles being produced in-house, the Air Force and Navy would be free to expend their arsenal in providing realistic training to their pilots.

A Ramjet-Powered Missile Is The Next Frontier

A weapon based on the Solid Fuel Ducted Ramjet (SFDR) technology would

add a new dimension to this capability, equipping the IAF with a missile with even greater range than the Astra, as well as superior end-game kinematic performance.

The key to achieving this leap in performance lies in a new form of propulsion called a ‘ducted ramjet’. Contemporary medium-range missiles are powered by conventional rocket motors. A few seconds after a missile is launched, its propellant burns out, leaving the missile to glide—or ‘coast’—to its target thereafter. As it coasts, it loses energy; and as it loses energy, it steadily loses the ability to keep pace with a target that is struggling to evade it. The further out the target is, the lower the probability of destroying it.

On the other hand, a ramjet motor burns for a longer duration, and can modulate its thrust over the duration of its flight. This translates to improved fuel efficiency, range, and energy retention. It is also capable of providing the missile with a burst of power (and agility) at the end of its flight, thus increasing its likelihood of intercepting a maneuvering target.

The capabilities offered by this technology are so transformational, that the Air Force insisted on acquiring the only operational missile based on it—

the MBDA Meteor—to equip its new Rafale multi-role fighters.

Efforts were also underway to mount it on the Tejas Mk.1A fighter, although they appear to have fallen through. Nonetheless, this setback will only be temporary. A similar

Indo-Russian initiative is already in development, and is showing early signs of success. In the future, it is likely that this programme (tentatively called the SFDR) will provide a homegrown solution in the Meteor’s stead.

The Road Ahead

The induction of the Astra, ASRAAM, Meteor, and a eventual SFDR-based missile will be a generational leap for an IAF that for years has made do with below-par air combat weaponry. Still, it would be prudent to exercise caution. The Astra may be close to the finish line, but the ASRAAM purchase may yet be stymied by a last-minute breakdown in negotiations. And the SFDR’s development is bound to take several years. It is a new technology, and has only been demonstrated in two tests from a ground launcher. If the DRDO receives the go-ahead to use it as the basis of a full-fledged AAM programme; the design, development, testing, and eventual transition to mass-production would follow a long trajectory. It took the Astra missile thirteen years to go from first test to limited production—with two design changes extending the timeline well beyond what was originally envisaged. It may well be a decade before the SFDR enters operational service.